How does ventilation work? All our homes are ventilated, but for most of us ventilation isn’t something we think about—it’s something that just happens. Without ventilation, the air inside our homes would become stale, CO2 levels would rise (from us breathing), and eventually we would become drowsy.

Out homes have traditionally been ventilated by just allowing gaps in the structure of the house. In stone built houses, for example, there are usually gaps between the windows, doors and the walls. There are gaps at the eaves of the property allowing air into attic spaces, and—if you have a chimney—you have a great big hole in the middle of your house that lets in air. You might have a letterbox. And some houses have ventilation bricks to allow air to enter a house. Another source of ventilation is leaky attic hatches and windows often have “trickle vents” included that you can open and close to allow air into a property. All of these sources allow air to enter your house, freshening things up and getting rid of stale air.

We measure the amount of ventilation in a house through “air changes per hour.” To measure this, a house is put under pressure—usually with a special fan that fits inside your main door’s frame, blowing air into a house (50 pascals of pressure—about what you’d experience during a windy storm). The measuring device is then used to measure how much air needs to be added to the house in order to keep it at this pressure level, and this gives us the number of “air changes per hour” that the house allows under normal use.

Its hard to give an exact figure for how many air changes per hour a house needs to reach, but in general terms, the less air changes per hour, the less energy you lose via ventilation, but also the less fresh the air in your house will be as there will be less fresh air coming in. A general ventilation standard for homes recommends four air changes per hour in order to maintain indoor air quality.

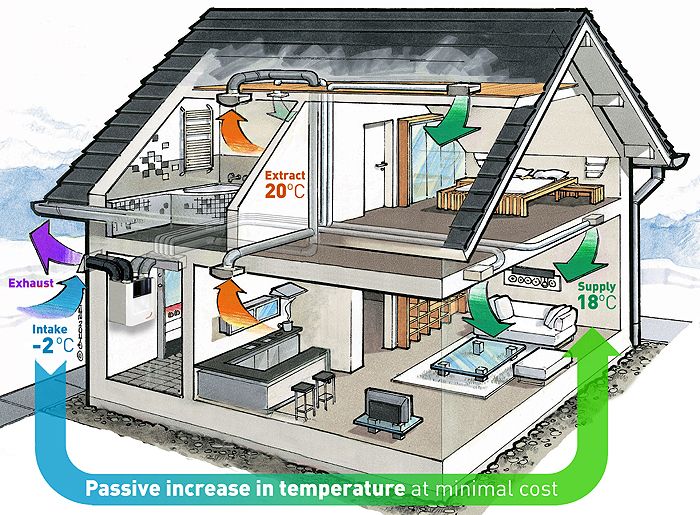

Working out the optimal rate of ventilation is about balancing reducing energy losses while ensuring that the interior of the property is pleasant and healthy to live in. Reducing energy from ventilation requires us to make choices. If we want very fresh air, we will lose more heat, which will cost us. This is why we shut our windows, use draft excluders and so on during cold periods – we make our house snugger, and so it gets warmer while costing us less to heat.

But this will have an effect on the air quality in a room. Ever notice how, when you shut all the doors, use a draft excluder, and whack the heating up, you start feeling sleepy? It’s the CO2 that makes us drowsy.

We now have 3 options. The first two choices are simple—either we have nice fresh air in the house but it costs us a fortune and/or makes the house very cold, or we have stale and not very fresh air while having a warmer and slightly cheaper to heat house. The third option is to use some sort of device to bring in fresh air, while helping reduce heating costs. I will discuss a couple of these devices in the next post.