A damp building is not a healthy building: damp and mould can cause respiratory conditions and allergic reactions to eyes and skin. Yet many homes and buildings in the UK manifest signs of dampness including mould and higher dust mite populations. According to the End Fuel Poverty Coalition, a third of the UK population experiences mould in their homes. The cause of damp homes and buildings is usually a combination of climate, type and quality of construction, and poor ventilation. A property owner or building developer cannot do much to change the climate but they can make choices about building model and ventilation that can prevent a building becoming damp.

Ventilation and moisture:

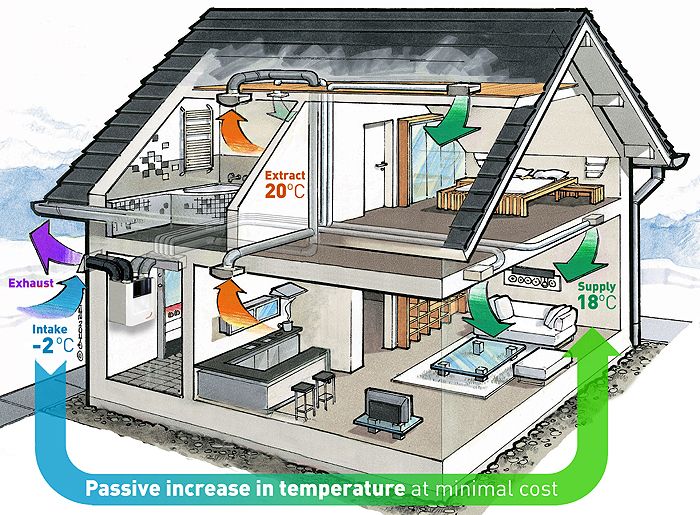

If the amount of moisture produced in a building by the daily activities (for example, drying laundry, boiling foods and kettles, baths and showers) is not balanced by the rate at which this damp air is removed and replaced by dryer outdoor air then indoor air will be more humid than it should be. And this is the situation in much UK housing: moisture production levels are high while ventilation rates are low. It is recommended that humidity does not rise above 60% for any “substantial” amount of time and at 70% humidity mould will grow. Sadly, in many homes in the UK (even new builds), humidity often reaches 65 or 70%.

Cold homes and moisture:

A building without sufficient insulation or a house that is very leaky or has a number of thermal bridges (cold spots caused by poor design or construction) will be colder and more expensive to heat. When temperatures fall, the risk of condensation increases, especially on or near cold surfaces, thereby increasing moisture levels and risk of damp and mould. Many of us are used to seeing the condensation on our windows as soon as the outside temperature starts dropping in the autumn. When a home owner is trying to keep their costs low by under-heating the house, colder surfaces (such as hard, ceramic or metal surfaces in bathrooms and kitchens) will also suffer condensation when moisture is generated. Also, a homeowner in this situation is likely to close up sources of ventilation (such as trickle vents), wanting to avoid the feeling of draughts of cold air on their body or in a room, thereby adding to the problem.

So, in order to tackle too-high levels of moisture in buildings, we need to:

ensure good ventilation . . .

in buildings that are cheap to heat to a comfortable temperature . . .

and in buildings that are free from draughts and thermal bridges.

Check back to the article “what is a passivhaus—technical answer” to find out how building to the passivhaus standard ticks these boxes.

For a much more in-depth look at this topic check out the Passivhaus Trust’s excellent paper on heath and wellbeing in buildings:

https://www.passivhaustrust.org.uk/UserFiles/File/research papers/Benefits technical/Health wellbeing and people performance v1.1 230810.pdf